I'd like to preserve some information that’s at risk of being destroyed by capricious billionaires: Ryan Kaufman's brief list of narrative choices.

Choices to access content

Extreme versions are just “choose ‘yes’ to continue.” (See also: Dragon Warrior’s infamous “But thou must!”)

Less extreme versions gate off side content — something like asking the player if they would enjoy a game of chess. Kaufman noted that most players don’t get much value from choosing NOT to do something.

Instead, these choices can become opportunities to provide an "active no" that reveals additional details about a story and its characters:

Choices to express an opinion

I’m ambivalent about reflective choices — asking players how they feel about things — because I can’t think of any times when they improved my enjoyment of a game. Cat Manning has explained that it takes an awful lot of work to do them well.

On Twitter, Kaufman also pointed out that there are risks involved:

The worst abuses are authors using “how do you feel about this?” in place of “choose ‘yes’ to continue.” The story moves forward on rails regardless of how the player feels about it.

Kaufman’s recommendation was to link these choices with actual changes in the narrative, possibly adjusting the character’s inventory or abilities to reflect their answer.

Choices for a secret, third thing

My favorite segment was the choice to keep another character’s secret. This happens in Outer Worlds, where the main character has several opportunities to turn Phineas Welles over to the authorities. (That game had some problems, but choosing to reveal the location of Welles’ base had significant implications for the story and the main character’s role in it.)

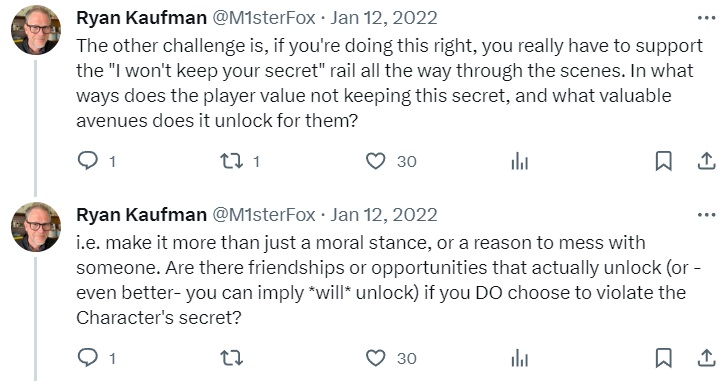

Kaufman pointed out that these choices should be introduced early, because the decision to reveal a secret has more emotional weight if the player has been keeping it for a while.

Building on these choices can add new dimensions to a narrative, especially when the different types of choices are connected. Choosing to keep a secret can lead to follow-up choices that ask how a player feels about their actions.